|

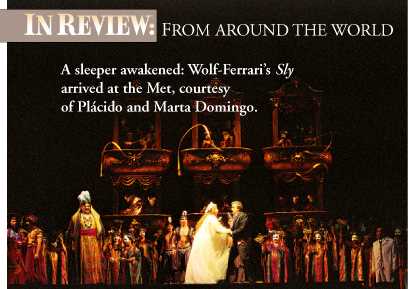

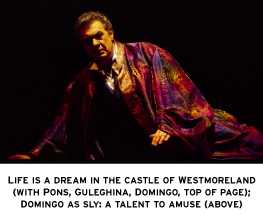

By JOHN W. FREEMAN Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's Sly, one of the novelties of the 1927 season at La Scala, had a distinguished premiere there, with Aureliano Pertile and Mercedes Llopart in principal roles, Arturo Toscanini conducting and Giovacchino Forzano, who wrote the libretto, in charge of the staging. The fact that Forzano was a member of La Scala's management team eased the work's acceptance by the Milanese theater. Similarly, Plácido Domingo's eminence on the Met's roster was responsible for this opportunity to bring Sly to New York (April 1), in a production that originated (with José Carreras) three years ago at Washington Opera, of which Domingo is artistic director. Sly in 1927 was less "modern" than several of its recent predecessors on the stage of La Scala, such as Pizzetti's Dčbora et Jaéle and Puccini's Turandot. Today, it sounds akin to Menotti. In subject matter, it overlays a stock Romantic preoccupation (the plight of the alienated artist) with a sprinkle of lately discovered neuroses (Freud had become fashionable). Though Wolf-Ferrari was half German, his stylistic preference was for the vernacular of verismo, rather than the twists and turns of Expressionism, which more venturesome composers were applying to similar subjects around that time. Strauss in Die Ägyptische Helena, Schreker in Die Gezeichneten and Zemlinsky in Der Zwerg all cooked with more paprika. But the staples of the stew remain the same: reality and illusion are fatally confused, while a perverse prank propels the plot and exotic trimmings garnish its stage picture. The spark plug of the Sly story is a cruel trick played on Christopher Sly, an alcoholic poet in the Hoffmann mold, by the sadistic Count of Westmoreland, who functions the way Hoffmann's nemeses do in the Offenbach opera. In an elaborate charade, the passed-out poet is carried off to Westmoreland's castle, where he revives in a fairytale stage setting designed to make him think he's a rich lord recovering from years of amnesia. Sly is then thrown contemptuously into the wine cellar. As a literary conceit, it's fraught with intimations of deeper meaning, but on the realistic level, Forzano and Wolf-Ferrari had difficulty making their characters believably human. The Count is just another two-dimensional villain. His mistress, Dolly, functions as little more than a projection of Sly's craving for sympathetic feminine companionship. The title role calls out for something positive to assert. Unlike, say, Canio's jealousy crisis in Pagliacci, Sly's dilemma lacks gut credibility. Beyond a knack for amusing his friends, he has shown no signs of talent, and his creative suffering seems to consist entirely of terminal self-pity.

Plake's Shakespearean costume was the only link to The Taming of the Shrew, the (frequently excised) prologue of which suggested the Sly story to Forzano. Otherwise, this staging places the opera in the 1920s of its composition, though the locale is still London. The use of a scrim creates an appropriate sense of unreality, furthered by the darkness of the sets. Marta Domingo, the tenor's wife, in her Met debut as stage director, has shaped Sly in groupings and gestures as conservative and traditional as the work itself. Michael Scott's designs -- atmospheric in the dingy tavern, glitzy in the movie world of Westmoreland's pleasure palace, stark and semi-abstract in its wine cellar -- offered costumes as moody as his sets. He used redemptive white to single out Dolly in Act II and the Angel of Death (danced by Christine McMillan) in Act III. Marco Armiliato coaxed a full palette of colors from the orchestra, never letting things drag, phrasing gracefully, supporting the singers as Wolf-Ferrari knew well how to do. Copyright © 2002 The Metropolitan Opera Guild, Inc. |

|

OPERA REVIEW | 'SLY' A Sad Tale, a Footnote, Rarely Seen By ANTHONY TOMMASINI The Metropolitan Opera owes Plácido Domingo big time. For nearly 35 years he has given more to the Met than to any other company. So when Mr. Domingo, who runs the Washington Opera, urged the Met to import his company's 1999 American premiere production of "Sly," a little-known 1927 opera by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari — a production directed by his wife, Marta Domingo — naturally the Met agreed, especially since Mr. Domingo would sing the title role. Call it nepotism, if you must. But hasn't Mr. Domingo earned the right to do just about anything he wants to at the Met by now? "Sly" arrived on Monday night. Though hardly some neglected masterpiece, it's a good example of the kind of solid, professional operas that were routinely produced by capable composers for the opera-mad public of the time. Wolf-Ferrari straddled two cultures. Born Hermann Friedrich Wolf to a German father and Italian mother in Venice in 1876, he added his mother's maiden name to his own, eventually calling himself Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari. An ardent Wagnerite, he attended the music academy in Munich where a conservative composition teacher tried to rid him of modernist tendencies. His first successful operas were lighter works that attempted to reinvent the comic Italian opera tradition for modern times. Wolf-Ferrari eventually fell in with the verismo movement. "Sly" came after a crisis period when he was distraught to see his two homelands at war. The character of Christopher Sly appears briefly in the opening scene of Shakespeare's "Taming of the Shrew." Giovacchino Forzano's libretto turns Shakespeare's tinker into a debt-ridden, hard-drinking poet and balladeer, whose songs delight the rowdy crowds at the Falcon Tavern in London. When the Count of Westmoreland discovers his mistress, Dolly, among the revelers one night, he decides upon an elaborate trick: his servants carry the passed-out Sly to the count's castle, dress him in finery and then pretend, when he comes to, that he is the count, arisen from a long illness. Dolly pretends to be his wife. After the hoax is revealed, poor Sly, locked in a wine cellar, slashes his wrists, visited, alas too late, by Dolly, who actually did love him. So it's not "Otello." But the story allows Wolf-Ferrari to explore psychological terrain touched upon powerfully by Offenbach in "The Tales of Hoffmann." Sly is a Hoffmann-like character, a poet and dreamer out of place in the world. Hoffmann was one of Mr. Domingo's greatest roles. So his attraction to Sly makes sense. That said, the opera never convincingly balances the tragic and the comic. It begins grippingly, with a tremulous sustained pedal tone shimmering in the strings as fleeting melodic fragments and wayward harmonies intrude. Once the tavern scene begins, though, the music lacks profile, until Sly, who arrives already drunk, is urged to sing his song about the romantic frustrations of a dancing bear, a wonderfully strange Hoffmann-like aria. In the next scene, when Sly collapses into bitter loneliness, the opera's major weakness becomes clear: you never understand the source of Sly's despair. If he's just a sloppy drunk, why doesn't someone rush to him and say, "Buck up"? If he's truly in delirium, shouldn't the revelers seem shaken? It didn't help that Ms. Domingo has everyone sit unresponsively around the tavern tables like clumps of lint. The music gains effectiveness as the tragic dimensions of the story take hold. The final scene in the wine cellar is a tormented soliloquy that Mr. Domingo made the most of. With these performances (José Carreras sang the role in Washington), Sly becomes his 119th role. Now 61, Mr. Domingo throws himself into it with his typical energy and charisma and sounds great, singing with vigor, gleaming colors and incisive rhythm. Though Ms. Domingo, a former soprano, has only been directing opera since 1991, over a long career as helpmate to her husband, she has seen it all. We see it all in this production, which is rather like a grab bag of traditional devices, with sets and costumes by Michael Scott. Ms. Domingo updates the setting from 1603 to the 1920's. Still, the staging is old-fashioned, favoring stand-and-deliver blocking. There are exotic dancers out of the Arabian Nights for the deception scene at the palace, and crooked walls in the wine cellar to signify the breakdown of moral order and of Sly's psyche. The lighting has been newly designed by Duane Schuler. Though it gets tiring to watch the action through a cloudy scrim all evening, it does give the show a unified look, with gleaming windows and wine bottles shining through the pervasive, murky greenness. The soprano Maria Guleghina brings her powerful voice and presence to the role of Dolly, and the baritone Juan Pons makes a suitably huffy count. Jane Bunnell as the tavern hostess and John Fanning as the actor John Plake, Sly's loyal friend, are very strong. Marco Armiliato conducts an assured and stylish performance. "Sly" holds few secrets. Hear it once and you've got it. But it was good to hear it once. This was the Met's first presentation of a Wolf-Ferrari opera in 75 years. Don't expect another soon, unless, say, Cecilia Bartoli decides she wants to sing "Il Segreto di Susanna." |

April 4, 2002 A Musty Revival's Anything but 'Sly' Domingo's an A in a B-opera By Justin Davidson

SLY. Music by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, libretto by Giovacchino Forzano. Production by Marta Domingo. With Maria Guleghina, Jane Bunnell, Plácido Domingo, Juan Pons and John Fanning. Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Marco Armiliato. Attended Monday's opening. Metropolitan Opera, Lincoln Center. Repeated tomorrow, Monday and April 13, 18, 24, 27, 30 and May 4. PLÁCIDO DOMINGO, having attained a level of stardom where he can have anything he wants, has chosen to mount an opera about a man who gets everything he wants - for an hour or so, before it dissolves into a cruel mirage. Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's "Sly" is a leaden parable swathed in a woolly score from the 1920s, and we have the tenor to thank for its disinterment. The production, which stars Domingo and was directed by Domingo's wife, Marta, comes to the Met from one of the two major American companies Domingo runs, the Washington Opera. (The other is the Los Angeles Opera.) It's a wonder he didn't leap into the pit to conduct the thing - but no, that thankless job was left to Marco Armiliato. Domingo sings the title role, a genially entertaining lowlife who passes out in a bar and becomes the slumbering plaything of a bored aristocrat. The Earl of Westmoreland, sung by the over- starched baritone Juan Pons, costumes the bum in regal silk and installs him in his own palatial bed. The fatally un-clever Sly wakes up and is quickly, though temporarily, convinced that he is really a nobleman, now suddenly emerged from a decade-long bout of alcoholic insanity and blessed with a beautiful, loy- al wife (actually the earl's floozy, Dolly). Subtler talents might have made this material into a gothic exploration of people's fluid identities - how unresistingly we allow ourselves to be shaped by what we are told. But librettist Giovacchino Forzano was no Edgar Allan Poe, and the closest Wolf-Ferrari's score gets to profundity is a deep honking of horns. So let's dispense with meaning: "Sly" is nonsense, but amiable nonsense, a sentimental melodrama in the style of early Hollywood, a B-opera if ever there was one. The opera seems defensive about its stolidity. In the first minutes, Maria Guleghina, as Dolly, makes a grand, Ziegfeld Follies-style entrance, sashaying down a staircase into the gloom of Sly's favorite haunt. Splendidly arrayed in a plumed hat and equipped with a glittering soprano, Dolly is searching for an authentic London dive. The place is lively? she inquires. "The music's not boring?" Actually, ma'am, I'm afraid it is. The score is a hodgepodge of ominous rumblings, quasi-modern outbursts, comic banter and full-throttle lyricism, stirred together into an insipid score, insufficiently salted with imagination. Creaky though it is, "Sly" performs well enough as a vehicle for the ever-youthful, indefatigable and musically voracious 61-year-old Domingo. He remains astonishing, his voice still steeped in sunny Madeira sweetness, his manner still convincing as a good-hearted, rubber-spined old boy with unfortunate judgment and a weakness for impulsive behavior (like, say, Don Jose or Alfredo Germont). But Marta Domingo makes the mistake of taking it all too seriously - lugubriously, in fact. Designer Michael Scott's bottle-green tavern hints at the source of Sly's misery, as if that weren't clear enough, and the director appears to have forbidden the customers from appearing to have any fun. For the second-act hoax, she has Scott dress the household staff in harem livery, with lots of Oriental chiffon and wiggling navels. That would certainly confuse the poor man: Not only does he wake up rich, but he has also apparently been reincarnated as an Eastern potentate. Perhaps the tenor has his eye on a little country he'd like to run when he retires from thestage. Copyright © 2002, Newsday, Inc. |

Apr 9, 2002 THE ARTS | OPERA NEW YORK Vanity affair keeps audience away By MARTIN BERNHEIMER Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's Sly, based loosely on a minor incident in Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew, was first performed in Milan back in 1927. A reasonably mellifluous if rather tedious and tawdry exercise in neo-romantic regurgitation, it soon achieved the oblivion it so richly deserved. Last week, an unreasonable facsimile of the same lame opera materialised at the mighty Metropolitan, suggesting nothing more than a vanity affair in the house of Domingo. Placido Domingo sang a somewhat simplified version of the Hoffmannesque title role, inherited from another twilight tenor, Jose Carreras. Marta Domingo, Placido's modestly talented wife, served as director. Their costly and pretentious ego-indulgence, borrowed from the Washington Opera, probably won't be around for long. Even with a beloved superstar, the Met couldn't sell out the first night. There's no need to go into much detail here. Wolf-Ferrari's cumbersome cliches invoke second-hand Puccini with a German accent. Marco Armiliato, the conductor, tried valiantly to deflect the inherent deficiencies with loud decibels and frantic motion. Placido Domingo sang the low-lying platitudes of the inconsequentially tragic hero with automatic-pilot warmth. Maria Guleghina exuded conscientious sympathy despite some strain as the heroine with a heart of tarnished gold. Michael Scott provided vulgar costumes and intermittently literal storybook sets. Marta Domingo's pretty-pretty stage-pictures offered crowd-scene muddles, a cheap musical-comedy ambience and one bizarre invention: an intrusive ballerina identified in the programme as the Angel of Death. Veiled and tutued, she tippy-toed her way through the last act like a Queen of the Wilis who had bumbled into the wrong provincial show. Copyright © The Financial Times Limited 1995-2002 |

|

Sly, mon mari! Ermanno. Wolf-Ferrari est aujourd'hui un compositeur bien oublié, dont quelques amateurs ne connaissent que deux comédies "Il Segreto di Susanna" et "I Quattro Rusthegi î. Le besoin pour certains ténors finissants de trouver des oeuvres à la mesure de l'usure de leurs moyens, nous vaut la résurrection de "Sly î, ouvrage monté il y a qualques années pour José Carreras, et tout récemment pour Placido Domingo dont c'est le 119 ème rôle. Allemand par son père et italien par sa mère, Wolf-Ferrari est un homme entre deux cultures: wagnérien de coeur, ayant étudié la composition à Munich, son "Sly î, qui vient après ses premiers ouvrages légers, subit l'influence du vérisme triomphant. L'ouvrage n'étant guère connu, je ne crois pas inutile d'en résumer le livret: Acte I.

Acte II.

Acte III.

"Sly" restera difficilement comme un chef d'oeuvre outrageusement négligé : c'est néanmoins un ouvrage solide, attachant, qu'on peut bien entendre une fois ou deux dans sa vie de mélomane. Il faut dire qu'on ne sait pas trop ce qu'on regarde. Le livret est typiquement vériste, mais la musique reste assez classique, plus proche d'ailleurs de la déclamation de Moussorgsky que de Wagner. Les premier et deuxième actes sont dans la veine tragi-comique ; le troisième est franchement noir : le soliloque de Sly contraste avec l'agitation du début (je vous renvoie à la distribution ci-dessus pour les seconds rôles intervenant au premier acte !). Sans doute des écoutes successives permettraient-elles de corriger ce jugement. Martha Domingo, ancienne soprano-ayant-fait-un-peu-d'études-de-théâtre, s'est mise à la mise en scène il y a une dizaine d'années : elle reconnaît humblement qu'elle le doit au nom illustre de son mari. Sans être révolutionnaire (du moins vue par des européens), et malgré quelques emprunts, cette production n'est pas indigne et tranche avec les productions réalistes récentes du Metropolitan : elle réussit à donner une certaine homogénéité à l'ensemble, dans une approche privilégiant le côté poétique. Pour l'occasion, Placido est en grande forme : le rôle n'est pas très long, la tessiture lui convient (encore que je suis prêt à parier qu'il y a eu quelques aménagements). Pour l'interprétation, on se contentera d'une resucée d'Hoffmann. Maria Guleghina n'est pas trop à l'aise : pour elle, le rôle est au contraire un peu trop grave (par voie de conséquence, elle a du mal à sortir son aigu final). Juan Pons est au contraire très à l'aise, campant un personnage ionique et irresponsable. Marco Armiliato se voit confiée la direction de cet ouvrage assez difficile à mettre en place et s'en tire remarquablement bien. SLY ovvéro la leggende del Dormiente Risvegliato

Placido Carrerotti |

New York City

New York City Wolf-Ferrari's music, piquant and emotional as a film score, is put together with professional fluency and security. He gives the singers plenty of free rein, building each act around an effective focal point -- Sly's ballad about a performing bear in Act I, his duet of awakening love with Dolly in Act II, his long monologue in Act III. The Met cast the work from strength. Domingo, deeply committed to the role, gave it his full range of mature resources as a singing actor. The tenor's clearly articulated voice and stage persona caught the tone of each act -- down and out in the first, confused but hopeful in the second, suicidally depressed in the third. He had a worthy partner in Maria Guleghina, whose strong, penetrating timbre, albeit with patches of reckless vocalism, conveyed passion and conviction. Juan Pons cut a satisfyingly nasty figure as Westmoreland, sounding out the role's arrogance, condescension and hypocrisy. Equally fine were Jane Bunnell as the harried Hostess of the Falcon Tavern and John Fanning, who strutted and fretted with a touch of old-fashioned operatic fustian as a Shakespearean actor, John Plake, ringleader of the tavern's literary crowd.

Wolf-Ferrari's music, piquant and emotional as a film score, is put together with professional fluency and security. He gives the singers plenty of free rein, building each act around an effective focal point -- Sly's ballad about a performing bear in Act I, his duet of awakening love with Dolly in Act II, his long monologue in Act III. The Met cast the work from strength. Domingo, deeply committed to the role, gave it his full range of mature resources as a singing actor. The tenor's clearly articulated voice and stage persona caught the tone of each act -- down and out in the first, confused but hopeful in the second, suicidally depressed in the third. He had a worthy partner in Maria Guleghina, whose strong, penetrating timbre, albeit with patches of reckless vocalism, conveyed passion and conviction. Juan Pons cut a satisfyingly nasty figure as Westmoreland, sounding out the role's arrogance, condescension and hypocrisy. Equally fine were Jane Bunnell as the harried Hostess of the Falcon Tavern and John Fanning, who strutted and fretted with a touch of old-fashioned operatic fustian as a Shakespearean actor, John Plake, ringleader of the tavern's literary crowd.