|

Wednesday June 11, 2003 OPERA REVIEW | LES BORÉADES Love Wins Out Against the Gods By ANTHONY TOMMASINI

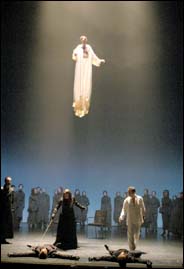

Just moments into the overture of Rameau's miraculous final opera, "Les Boréades," at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Monday night, you knew you were in for a long, full evening of utterly vibrant music making. Under the conductor William Christie, an incomparable interpreter of this 18th-century French master, the musicians of Les Arts Florissants brought crackling rhythmic brio to the jaunty music. With two Baroque horns playing hunting calls from a low balcony to the left of the pit and two Baroque woodwinds erupting in dizzyingly virtuosic flights from the opposite balcony, you experienced the French Baroque equivalent of Surroundsound. The curtain went up to reveal the opera's distressed heroine, Queen Alphise of Bactria, in a dowdy blackish dress and high heels walking against a surreal sky blue backdrop amid a field thick with oddly stiff-stemmed flowers of every color. It was immediately clear that the director Robert Carsen, with sets and costumes by Michael Levine, had devised a playful modern-dress concept for this mythological story that also tapped its dark subtext. The production, given its premiere at the Paris Opera in March, is only the third staging ever of Rameau's posthumous "tragédie lyrique." The additional performances at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Opera House tonight, Friday night and Sunday afternoon offer rare opportunities to revel in a beguiling presentation of a staggering masterpiece that has come to light only in the last 20 years. "Les Boréades" poses the question of whether the winds, storms and floods represent the attempts of the gods to coerce human behavior or whether these natural elements are metaphors for human emotions that are equally awesome and unruly. Fate decrees that Alphise must marry a descendant of Borée, god of the north winds. Two princely suitors who meet the test, Calisis and Borilée, pressure the queen to make up her mind and provide a king to her worried people. But Alphise loves Abaris, a man of unknown parentage who has been raised by the high priest Adamas in the temple of Apollo. When the queen decides to forsake her throne and marry the man she loves, the gods unleash torrents of horrific weather as a punishment, or so it seems at first. Mr. Carsen fills the stage with effects that suggest thick fog, howling winds and blistering snows. The elements are captured with special-effects exactitude in Rameau's orchestra. Not even Vivaldi in "The Four Seasons" did a better job at conjuring hail storms, thunder and, in contrasting moments of calm, rippling brooklets and harmonically radiant bursts of sunlight. In this production the Boréad suitors are backed up by attendants similarly garbed in gray suits and overcoats and carrying, in place of swords, umbrellas. But our sympathies are meant to go to the followers of the high priest, who support the claim of Abaris and urge the queen to follow her heart. That's the way the disciples live as well, for when we meet them they are dressed variously in white underwear and nightshirts, and nestling in loving couples atop a stage thickly strewn with autumnal leaves. Mr. Christie has long attracted young, eager singers to Les Arts Florissants who are keen about acting and movement. These attractive and limber choristers could easily be mistaken for dancers, as they execute the athletic steps devised by the choreographer Édouard Lock. But Mr. Lock's choreography for an agile roster of solo dancers may divide opinion. He has responded to the tensions that lie below the surface of Rameau's courtly, rustic and pastoral dances by devising tightly wound, hyperkinetic movements for the dancers, who spin and turn, all jittery and mechanistic, with fidgety arms and kicking legs. Moments of confrontation between the forces in the story are poignantly rendered. I'll not soon forget the scene when a line of gray-cloaked attendants to the queen's suitors appear at the temple of Apollo with brooms; they ruthlessly sweep away the fallen leaves and push apart the lovers. In the end, Apollo himself appears from on high to reveal that Abaris is his son, begotten of a nymph in the line of the Boréas. When Rameau composed this score in the early 1760's, Gluck was reforming opera and Haydn had appeared on the scene. On its surface the score may seem a throwback to a dated Baroque style. But just below its surface the music abounds with Rameau's ingeniously rich harmonic language and endless melodic inventiveness. His conversational and engrossing approach to recitative was also enormously innovative, and he seamlessly weaves a fabric of arias, recitatives and dances. True to the coaching of Mr. Christie, the winning cast members — headed by the soprano Anna Maria Panzarella as Alphise, the tenor Paul Agnew as Abaris, the tenor Toby Spence as Calisis and the baritone Jean-Sébastien Bou as Borilée — bring stylistic insight, clear French diction and vocal ardency to their performances. Mr. Christie is a formidable taskmaster who demands unrestrained commitment from his singers. What that meant on this night was that at times these young voices sounded pushed. Perhaps this was because of opening night excitement. Still, the singing was energetic and involving and was rightly rewarded with ovations. The staging ends with a lovely image. As Alphise and Abaris embrace, their love now sanctioned by Apollo, it starts to rain, with real droplets falling. This time the natural elements seem a gentle blessing. |

|

FINANCIAL TIMES Opera: Les Boréades By Martin Bernheimer Les Boréades , Rameau's final opera, was written in 1763. The first full performance wasn't staged, however, until 1982 when Aix-en-Provence ventured its historic exhumation. The National Opera of Paris finally followed suit last March. Now its fanciful production has been transferred from the Palais Garnier to the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The odyssey only took 240 years.Rameau stretched far beyond period formulas in his ode to joy in the dark domain of Boreas, god of the north wind. The mythological plot may be severely convoluted, but it is elevated by music that often sounds progressive even to hardened 21st-century ears. The score unravels slowly over its three-and-a-half hour course, yet it abounds in expressive recitative, surprising melodic flights and jolting harmonic shifts. William Christie surveyed the inherent wonders on Monday with reverence that never precluded vitality. Some of his singers may have seemed a bit timid, and pitch problems occasionally plagued both stage and pit. Never mind. Such blemishes must come with the Baroque territory. Director Robert Carsen, who has staged a brilliant, quasi-minimal Evgeny Onegin at the Met, insists on giving Rameau's very old opera a brazen new look. It shouldn't work, but it does. Sensitively abetted by the designer Michael Levine, he stylises movement, freezes the action in moments of stress and dresses the cast in contemporary mufti. The critical changes of season are conveyed wittily, with full-stage onslaughts of flowers, leaves, snow and rain. The only serious miscalculation involves Edouard Lock's hyperkinetic dance numbers. It's as if a film were running fast-forward. The abandon is admirable; the contradiction of the musical pulse isn't. |

|

Classics Today CHRISTIE, CARSEN BRING RAMEAU’S BORÉADES VICTORIOUSLY TO BAM By Robert Levine Jean-Phillippe Rameau’s Les Boréades, composed in 1764, was cancelled during its rehearsal period upon the death of the composer; the first staged performance of the opera was in 1982. The production which opened at the Brooklyn Academy of Music last night and which will be repeated on the 11th, 13th and 15th (matinee) originated in Paris this past April. It was a critical and popular success there and it similarly bowled over the capacity audience in Brooklyn. The work is lightly plotted: Alphise (soprano), the Queen of Bactria, is supposed to marry one of the sons of Borée, the god of the north wind – either Calisis (tenor) or Borilée (baritone) – but she loves, and is loved in return, by a commoner, Abaris (tenor). There is great outrage – and storms galore – when she announces that she will abdicate to marry Abaris, and it is not until L'Amour intervenes and Apollo announces that Abaris is, in fact, one of his sons, that all is resolved. Despite the flimsy plot – on some level the opera is as much about weather as anything else – the marriage of spectacle, dance and song presents Rameau at his most glorious, with ravishing orchestration (four each of bassoons and oboes, pairs of clarinets, horns and flutes in addition to percussion and a grand complement of strings), exquisite melodies, complex vocal lines, catchy rhythms, plenty of choral interjections and heart-rending laments. More than almost anything else, the octogenarian Rameau appears to be bathing in the powers of music to express nature – both human and the other kind. Conductor William Christie and his group, Les Arts Florissants, in conjunction with director Robert Carsen, have brought the work, with all its anthropomorphic confusions, thrillingly to life. After a few tricky attacks by the difficult-to-play valveless horns, the musicians played splendidly for Christie, with utmost gentleness during the more introspective moments and in a handsome, controlled frenzy when Borée and his boys unleashed their fury. Carsen’s direction was witty and wise. Not only did he manage the changes in weather brilliantly – the disappearance of a huge bed of flowers led to a veritable downfall of autumn leaves which were elegantly swept away with oversized brooms; men crossing the stage spinning upturned umbrellas to release snow, and so on – he made us understand the nobility of Alphise, the desperation, sadness and eventual strength of Abaris and the rage of the rejected wind-brothers. Apollo descends from above, stage rear, swathed in white sheets, and extras, carrying knives and forks, enter to one of Rameau’s dances for the setting of an enormous dinner table. Édouard Lock’s choreography, while based in classical ballet, was danced in a manic, double-time; it could be somewhat nerveracking. The costumes by Michael Levine (also responsible for the fine minimalist sets) had the powers of wind and their court in Matrix-styled black and the Abaris/good guys in white underwear. I believe Christie’s concert pitch was close to a whole tone below A = 440, thus making it somewhat easier for the upper-voiced roles, which are written in a cruelly high tessitura, but at times, as a result, the lower voices seemed underpowered. Anna Maria Panzarella handled Alphise’s music well, she takes obvious interest in the text, and her vibratoless tone had just the right penetrating effect. Paul Agnew started off a bit roughly as Abaris, but settled into the high-flying role brilliantly; he managed the outbursts as well as the tender moments with élan. Toby Spence was spectacular as the angry Calisis, whose role sits even higher (and is more explosive) than that of Abaris; both Laurent Naouri and Jean-Sebastian Bou as his father and brother, respectively, had to work harder with their rich baritone voices. The rest of the cast, including a sweet-voiced boy soprano, Jason Goldberg, as L’Amour, were top-notch. Congratulations to BAM for making it all work. Tickets are going fast for this very special event and you have three more chances to experience it. New York had to wait 229 years to hear Les Boréades and it was worth the wait. Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York; June 9, 2003 |